American politics and bars share a long history

Generally, there are a few things that do not mix well at a bar. Politics, religion, and sports (even in a sports bar) when stirred up with alcohol. This is not just an election year. It’s a raucous election year that could have strong impact for decades to come. Thus, passions and tempers are heated, aside from being fueled by liquor, wine or beer.

From now through the top of November, these elections will be inundated with all sorts of political drama, some of which we might watch at a bar, such as news commentary, talk shows, or an actual debate between candidates.

And some of us might attempt to mightily avoid it all at a bar. Ironically, this political frenzy is not limited to this time and place. America’s earliest history and politics actually started in bars, or taverns as they were known then.

American Bars wrote about this early on. Truly, taverns and alcohol were the secret elixir that sparked American independence. Some of America’s most venerated political and military events were orchestrated from taverns.

If you would like to delve into this heritage of grog and government, there is a just-released book, “Taverns of the American Revolution” ($24.99), published by Marin County publisher Insight Editions, includes photos and essays, along with maps, period artwork and — especially for American Bars fans — period cocktail recipes.

After visiting old bars in the Sierras, Covert started wondering about the oldest bars in the United States, the taverns of the Revolutionary War period. After some preliminary research he discovered two things: A lot of the old historic taverns have survived, and not a lot has been written about them.

So Covert invested a year of research and by contacting various historical societies he finally worked up a list of 160 potential taverns. A three-week road trip through the Northeast whittled it down to 30.

“Most of the taverns still extant are outside of the major downtowns,” he says. “They are trapped in time and have survived, many of them beautifully so.”

Although he concedes a few have not: “One is a yoga studio and another is a Starbucks.” So Sad!

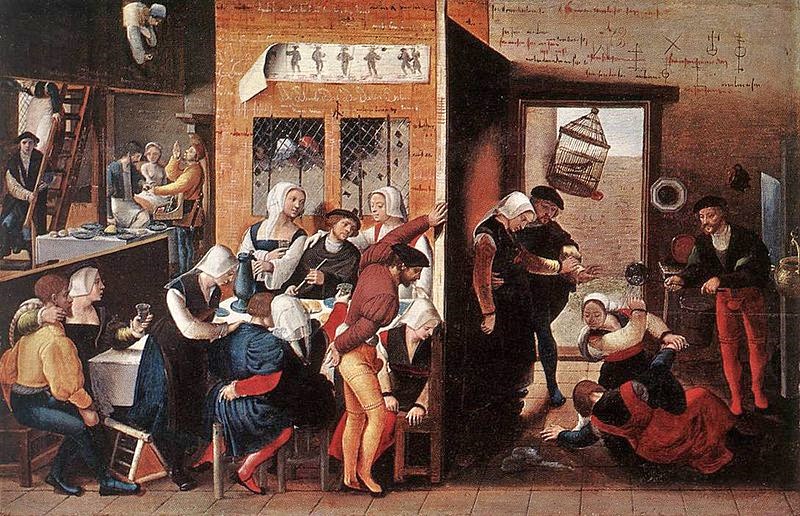

He concentrated his book on the historical ones still in use. Covert says that taverns back then functioned more like the living rooms of today.

“You had a fireplace, typically circular tables and chairs and then the bar, not a long table running down the length of the room, but rather a corner countertop wedged at a 90-degree angle in one corner of the room. Behind that countertop is where the booze was stored,” he says. “The word ‘bar’ comes from the hinged bars, hanging from the ceilings that were lowered when the tavern keeper had to step away.”

+Merry+Company.jpg)

Rum, ale, cider, wine and Madeira were typical fare. “Whiskey was not the beverage of choice,” he says. “Rum was the common distilled alcohol in the colonies. And the colonial economy relied in large part upon it.”

Covert contends that the molasses trade from the French Islands of the Caribbean allowed the colonists to distill cheap American rum that they then used to buy British manufactured goods, undercutting British interests.

“A big part of the war was started from that,” he says.

A series of taxes on molasses, sugar and then tea finally forced the colonists to arm themselves and resist.

“The whole Battle of Lexington and Concord was really a battle at several taverns,” says Covert.

Covert says that many historians suspect that the first shot of the American Revolution was actually fired from behind the Buckman Tavern. A shot that prompted the British to open fire and commence the armed conflict now known as the American Revolution.

Some other historical tidbits included in his book:

• The Boston Tea Party was planned at Boston’s Green Dragon Tavern, and afterwards the Tea Partiers returned there to celebrate.

• After Washington’s triumphant entry into New York City on Dec. 4, 1783, he went to Fraunces Tavern and informed his officers that he was resigning his commission. He also, tearfully, informed them that he had failed to secure the pensions from the Continental Congress for them that he had promised.

• Benedict Arnold’s co-conspirator, John André was jailed and finally executed at the Old 76 House in New York.

• The Virginia Colonial Legislature, which included George Washington, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, often retired to the Raleigh Tavern. And it was from there that they issued a call for the first Continental Congress.

For anyone interested in the politics of early America, or in early American bars, or both, Covert’s book is an excellent read. For those of you more interested in current politics, you can always turn on your TV…or the one at your local bar, if your in a fighin’ mood.